Chloe was a bit nervous as it was her First Washing of the Feet. The small church in Smyrna endured the vicissitudes of history and after 2000 years of history, was now the only church inspired solely by John’s Gospel in all Christendom.

First Washing of the Feet Day was the day in which Chloe would fully participate with the rest of the community, in the Eucharist. It was not an easy path. Chloe had to go through a very practical preparation, some special sessions on empathy, respect, acceptance...

She had to join several groups who would distribute food to some homeless in the big city, help at a dispensary in the sketchy part of town, participate and prepare a program for women’s empowerment, and still contribute as a volunteer in an environmental awareness project.

She felt how important this moment was: The big thanksgiving, the Eucharist. She wanted to make Jesus present in service as reminded by her, now almost memorized, through the Eucharist reading read a million times during every Sunday at the Eucharistic Gathering. The words of consecration. Jesus’ final action and instruction during the Last Supper: «After he had washed their feet, had put on his robe, and had reclined again, he said to them, “Do you know what I have done to you? You call me Teacher and Lord, and you are right, for that is what I am. So if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you John» (13: 12-15).

She liked it. In service and through service she felt connected to Jesus. It was not so much about creeds and dogmas; it was about a commitment to service. What a beautiful way to make Jesus present into the world!

Of course, Chloe knew about the other Eucharistic traditions originating from the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke.) She knew that for them the bread and the wine were at the center of the Sacrament. But Chloe always thought that the Johannine vision of the Eucharist, through the Washing of the Feet, was as meaningful, at least to her.

That Sunday when people lined up for the moment of the Washing of the Feet, Chloe was thrilled: Seven elders, at the back of the church, not wanting to be at the center, began washing the feet of the seven candidates, who in turn washed the feet of other seven people, and they washed seven more people, so that they all washed each other’s feet, as commanded by Jesus in John’s Gospel. The Eucharist took time, as it does every Sunday really. For Chloe though, it was a moment of commitment and a moment of joy. From that day on, service was to become central to her life, whether in the community, at the church or in her family. She knew that service was at the core of her faith. Service, she thought, is the way to bring Jesus to others and she felt ready for it.

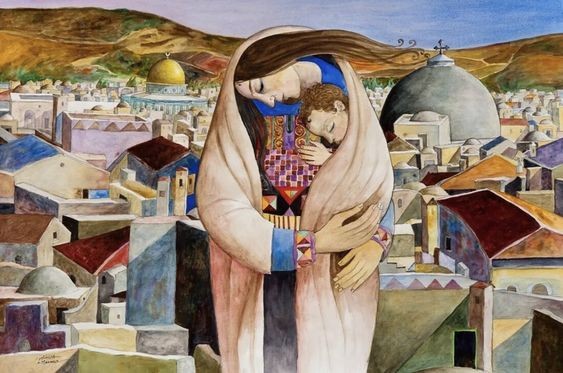

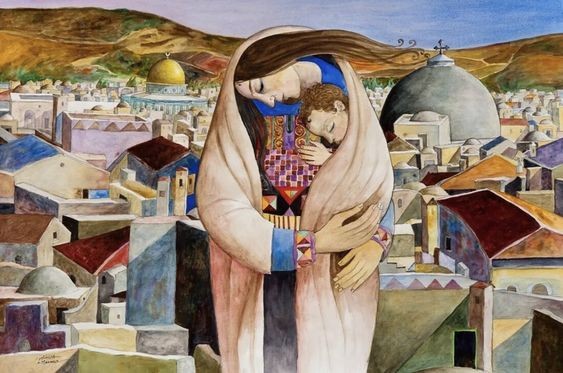

In the context of Mothers' Day, which we will celebrate this coming Sunday, we offer the following meditation.

I am not a mother, but I know how much pressure we put on mothers, as we usually point to them for their son’s and daughter’s success and, above all, failures. A mother’s love is instinctive which doesn’t mean necessarily that it comes from the heart, but, quite the opposite, it’s ingrained, and sort of imposed by their genes. A mother’s love, including, of course, adopting parents, is hardly chosen. It is the feeling of ultimate responsibility for their children regardless of their actions. Mothers are not always models of kindness and tenderness, but unless prevented by some health and mental illness, mothers embrace their children’s joys, and suffering and pains as those of their own.

In today’s wars and conflicts, thinking about mothers helps me to get some perspective beyond ideological or political views.

I think about the suffering of Ukrainian mothers as they see their sons and daughters being sent to war to defend their land, and (emphatic “and” here), I think about the mothers of the Russian soldiers also sent to kill and be killed in a war that they may not fully understand.

And I think about the mothers of those killed or held hostage by Hamas just because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and I feel equally for the mothers of all the Palestinians killed in the spree of violence (many who were mothers themselves.)

I refuse to make sense of explanations about political calculations, nationalistic motivations, historical legitimacies. And I refuse to rationalize about lesser evils or proportionate response. I choose to dwell in the suffering of all the mothers (and the fathers, and sisters and brothers and grandparents…). It makes it less simple than taking sides, but more human, less soothing but more empathetic.

I have sympathy for Russian mothers, and Ukrainian, and Israelis, and Palestinian mothers. Of course, I do have an opinion about some of these conflicts. But my reasoning, my ideological view, my political persuasion (that I undoubtedly have) will not make me feel that the death of a human being, the death of somebody’s mother or father, is politically necessary, morally deserved or justified.

No matter what side you are on, no matter what your ideological persuasion and what reasons you have for it; If we fail to feel the suffering of a mother in Ukraine, in Russia, in Israel, Palestine, or any mother and father who loose their children, if we fail to empathize with them, if indeed, we fail to empathize with any pain and suffering, our humanity will have surrendered and succumbed, to the world of ideas and politics. Thus, we will have turned our hearts into stones.

In the Passion Narrative, Jesus shows his radical vulnerability. He is crucified as a criminal abandoned by his disciples, in pain and in agony, mocked by Romans, rejected by Jews.

Jesus shows himself so vulnerable and powerless to the level of exasperation. We have a feeling that Jesus could have done more to avoid such pain. He is mocked and ridiculed, betrayed and denied, humiliated and tortured; even criminalized, and yet he does not do anything to avoid it.

Even at his last moments when torture is unbearable, He shows no indication that he will use a final ace (or superpower), to pulverize his enemies (maybe we’ve watched too many Hollywood movies.) In fact, not even during His Resurrection, does Jesus seem to care about making things right, about swift revenge for those who wronged him. At the Cross, Jesus is hurt physically, socially, psychologically, in all possible ways, yet he is there showing his weakness as if He chose the path of vulnerability.

There is a paradox in the Cross. On one side, the more vulnerable we are, or we want to become, the easier it is to be hurt. Vulnerability exposes us like Jesus was exposed publicly on the Cross. We can become the easy target of gossip, judgement, prejudice and punished to ostracism. But at the same time, vulnerability makes us free. Jesus was a free man because he did not intend to negotiate power-bargains with Jews or Romans. Jesus did not have to pretend; He literally had nothing to lose. He chose not to carry the burden (or the chains) to have to play the role of the tough guy, or strong leader, not even confident believer (remember his crushing words “Father, why have you forsaken me?”).

The church is not a community of the convinced, or self-righteous; it is the church of the vulnerable.

The church is the community of those who become free to show their miseries, shortcomings and inadequacies; Those able confide in others about their poor skills in parenting, or their mediocre professionalism or their selfishness as partners and recognize their flaws and poor choices. It is a risky business, we can get hurt, but the more we show our cross, the more we recognize our vulnerabilities, and the more we accept them, the easier it will be to heal them.

Making ourselves vulnerable creates a sacred space where we can show our doubts, our uncertainties, our wrong doings, our regrets, our frustrations. We all fail, and we tend to fail often. We can hide our failures, or we can show them and be naked in our personal shameful cross. We may be hurt, but we may also open a space for empathy

… a space for compassion

… a space where we are not judged

… a space for acceptance

where vulnerability begets empathy, and then trust and then, love.

In the classic film Gladiator, at one point one of the characters advises the gladiator —the man used to win his bloody fights with speed and ease— and tells him, «It is not enough to win: the public wants an spectacle. Win the crowd and you will win your freedom.»

This is what we largely remember, in a tragic and dramatic way, during Palm Sunday. Those who control the masses (in this case the religious hierarchies) hold the real power.

There is a sharp contrast between the multitudes that sing «Hosanna, hosanna!» and the masses that shout «Crucify him! Crucify him!»

Last Sunday we read the story of the adulterous woman, and it reflects what Jesus’ will really is: not to get lost in a crowd, but rather to assume our responsibility, to be able to think as individuals and discern our actions with humility, compassion, and tolerance. The worst abuses and sins are often committed in the name of parties or factions: inequality, poverty, injustice, racism, exclusion, intolerance, corruption, are most often carried out by masses immersed in sinful structures. How easy it is to fall into dynamics of abuse and intimidation, almost without realizing it, when we are part of an unthinking and often unjust crowd.

How beneficial would it be to remember Jesus’ words to the group of men who wanted to stone the adulterous woman: «Whoever is without sin may cast the first stone.» I wish that in the crowds of Jerusalem each person would have assumed his or her own responsibility and realized that what was taking place before their eyes was not so much a trial or a legal action against Jesus, but the lynching of a person who became a nuisance because, although he was a leader, he could not be controlled by the political or religious powers.

Let us not become crowds that abuse the vulnerable (be they immigrants, poor, refugees, minorities), blaming them for our misfortunes to ease our consciences. In his passion at the hands of an embittered mob Jesus became the scapegoat, especially for those who wanted to win the crows. Ironically, he also became the innocent victim who atoned for the sin of the world.

(Picture: The author, celebrating Palm Sunday in Sabana Yegua, the Dominican Republic).

There is no Christmas without Advent

There can be Advent without Christmas

Advent is necessary, but not enough

We need Christmas.

John the Baptist is necessary but not enough,

we need Jesus.

Mary is necessary but not enough,

we need her Son.

Repentance is necessary but not enough,

we need hope.

Prayers are necessary but not enough,

we need commitment.

Love of God is necessary but not enough,

we need our neighbors.

Love is necessary but not enough,

we need deeds.

Life is necessary but not enough,

we need dignity.

Unity is necessary but not enough,

we need solidarity.

Peace is necessary but not enough,

we need justice.

Tolerance is necessary but not enough,

we need communion.

The law is necessary but not enough,

we need mercy.

Words are necessary but not enough,

we need actions.

Respect is necessary, but not enough,

we need kindness.

Family is necessary, but not enough,

we need a village.

Yes, Advent is necessary, but we still need Christmas.

Messi left the F.C. Barcelona soccer team, and Barça fans—and perhaps the entire city of Barcelona—is now mourning this loss.

Messi is going to Paris to play for the PSG, earning EUR 36,500,000 ($42,769,240) per season, and that is without counting advertising contracts and other incentives he will receive. It is half of what he had been earning so far with the Barcelona FC.

Football star Aaron Rodgers will instead renew his contract with the Wisconsin Green Bay Packers for four years, for an annual average of $ 33,500,000 (EUR 28,589,067).

The average annual salary, not the basic one, in Spain is $31,561 in the USA is $62,953.15.

The average worker in Spain would need to work 1,355 years to earn what Messi will earn in one.

In the United States, the average worker would need to work "only" 635 years to make what the quarterback makes in one.

I am a fan of the Barcelona soccer team by genes, and of the Green Bay Packers by adoption, but when faced with these numbers I can only feel sadness, some anger and perhaps a bit of guilt, for harboring occasionally some resentment against the fans of my teams "eternal rivals,” the Real Madrid and the Bears, when the reality is that I have much more in common with the vast majority of them than with the stars of my teams.

There are gaps that should not be justified neither by nationalisms, nor by national or local loyalties, much less by the vicissitudes of the free market.

Congratulations, I’d like to say. But not to Messi or Aaron Rodgers. Congratulations to the thousands and millions of men and women who work hard and hard, sometimes with two or three jobs, to be able to support their families, year after year, with dignity.

There is a revealing factor in the metaphor for Pentecost. At his coming, the Holy Spirit fills the house with noise and wind. It then divides itself in tongues of fire descending on those gathered. This double movement resolves a dangerous dichotomy, namely, whether the Holy Spirit is a communitarian and global reality or a personal and individual experience.

There is no doubt that the experience of the Holy Spirit is a call to inner motivation, to the tireless search for enthusiasm and to go out to meet those who are different, those who speak a different “language” than ours. This is the movement of the Holy Spirit descending into each of us. The Holy Spirit has to touch our hearts.

But declaring oneself individually as “filled with the Spirit”, as opposed to all those who do not have it, it is a dangerous claim—one that easily leads to intolerance and arrogance. The indispensable requirement for the arrival of the Spirit is to be “gathered” together. First, the Spirit engulfs the house and only then descends on each of the disciples.

The Holy Spirit is a collective experience of the whole Church, and even outside of it. Pentecost is a communal feast. It calls for a personal commitment, but one that compels us to be an open Church. To be open to those who are not like us. The Spirit transforms the Church, so that it is her who wishes to be understood by others. She is not waiting for others to do the effort to adapt to her language. She rather strives to speak in the languages of the world.

The Holy Spirit breaks into the Church, and fills it all, and then inspires each one of us to open up to become closer to all, to make ourselves neighbors of others and thus become witnesses of Jesus’ love.

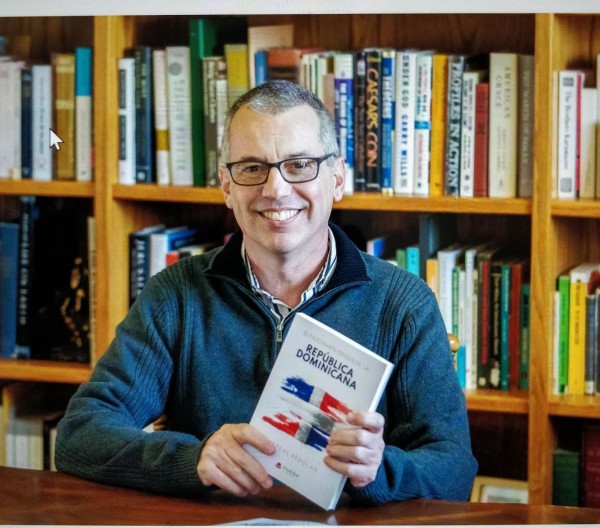

“Círculo Rojo” Publishing house, from Spain, has just published “El fascinante origen de la República Dominicana” (The fascinating Origin of the Dominican Republic) by Esteve Redolad, a member of the Community of Saint Paul.

The book combines historical rigor with a dynamic and entertaining reading. It is aimed at Dominicans, and all those who are interested in this wonderful country, and those who like history, especially Spanish colonization, slavery and Latin-American emancipation.

The book intends to question some myths, in which, as in most national narratives, “we” are inevitably the good guys and “the others”, the bad ones.

The book can be purchased in printed format at Amazon, Casa del Libro and the Círculo Rojo Publishing House and in digital format at the Casa del Libro, Agapea and El Corte Inglés.

Congratulations, Esteve!

https://editorialcirculorojo.com/el-fascinante-origen-de-la-republica-dominicana/

One of the critical characters of Palm Sunday is the crowd, the crowds. We do not know if they were two different crowds, one shouting Hosanna, and the other shouting Crucify him. The fact is that the crowds can be easily manipulated, as it happens in populist regimes that give bread and circus to the people in order to silence their critical voices and submit their will. On the other hand, crowds have a great influence on the development of a society, as in the case of popular revolutions.

Nowadays, of course, any reference to crowds has to do with the coronavirus pandemic. In this case, to what degree the attitude of the "crowd" may determine the development (or not) of a deadly disease. It is important to realize that what the multitude does depends on the attitude of each one of us. So, it is essential that we all, as individuals, act responsibly.

Misinformation is a huge factor that can come into play to manipulate the crowds. We live in a time when it is easy to be overwhelmed and even depressed by the amount of information we receive, to the point that at times we can’t distinguish between what is reliable information and what is not.

We receive information about a natural cure for the virus, about toilet paper’s fever, about political explanations, or about end-of-the-world religious-based arguments. Everything is mixed in this gigantic pool of information. We can blame the particular interests of the media, and we might be right, but that does not mean that we are exempt from our responsibility to be well informed. Traditionally, we distinguish between the inevitable ignorance that emanates from our own personal limitations, and the guilty ignorance: when it becomes very convenient for us not to know about certain things and let ourselves be carried away by the crowd. These days, we should fight against the latter, as much as we tenaciously fight against the coronavirus.

It is uplifting to see how at 8.00 pm in various corners of the world people go out to their balconies to applaud those who these days are hard at work so that life can be, if not normal, at least bearable.

Healthcare personnel, cleaning staff, supermarket stockers, vendors, drivers, loaders, post-persons... The coronavirus has brought to the forefront many of the jobs and workers that we normally take for granted but which today are, interestingly, considered essential.

This pandemic, in all its brutality and pain, has highlighted the degree of interdependence in our society. Society is organic, it is an organism in which all parts are equally necessary. All executives or bankers or shareholders in the world are worthless to me, if I don't have someone to take the food to the supermarket, or someone cleaning the bathrooms in Wall Street offices.

In the same way that the epidemic is total (pan-demia), hopefully we can recognize that society is not based on the ideas like the “survival of the fittest”, “every man for himself”, or the myth of the self-made person. We live in a pan-dependency (a total interdependence). Recognizing and accepting this will help us build a more egalitarian society.

We are in times of crisis. Difficult days for everyone. But perhaps, because of that, we are presented with a unique opportunity to practice the value that makes us, human beings, a unique species: solidarity.

There are times when we do not know how to be supportive, it is not always easy in a society as structured and legalistic as ours. But in these moments, to show solidarity is actually quite simple.

Act as you are the one who is sick: Do not treat others as if they were a threat that can infect you. Let's assume that we (each of us) are infected (we can be, but without symptoms), and we must prevent infecting others. Staying at home, not going out although we feel good, today it is a great act of solidarity.

Do not accumulate illogically: Panic is not going to help us. Accumulating without measure will always harm someone else. When the basic products are finished, those most in need will be the most affected. And besides, accumulating stuff is not necessarily better for us. It is an amusing irony that people want to accumulate masks and disinfecting products to save themselves, when in fact what would be most convenient for us, almost out of pure selfishness, is that others can be clean so as to not contaminate us.

Use your phones: In this time of social distancing, may our mission be to become aware of those who are most vulnerable. Let's keep an eye on our grandparents, our parents, our neighbors who live alone, the people who are sick. Let's call them, send them messages of encouragement, or jokes (good humor is good medicine). Let's ask them if they need something, that they know we think of them, and that we pray for them.

Let’s accept these difficult moments as an opportunity the show our most generous side.

Just as in Advent we prepare for Christmas, Lent is also a time for preparation. Lent is a time for reflection, time for analysis, time for honestly valuing our attitudes, our decisions, our commitment.

It is time to talk with ourselves and with God in prayer, sincerely, honestly, without cheating ourselves with excuses, or justifying our actions. It is time to recognize who we are without fear; of looking ourselves in the mirror, even though sometimes we may not like what we see.

We know that God does not punish, that He is always merciful. Let’s not be afraid, then, to recognize who we really are, remembering that we are all in the same boat. We are not divided in “good ones” versus “bad ones”, pure and impure, first or second-class citizens. We all share the same human condition, and through it we are all capable of acting generously and make the world a better place.

Likewise, we all have our miseries, our selfishness. Each one of us must discover these two dimensions. If I only see the negative aspects of myself and nothing positive, I will have to look deeper into my heart, and learn how to be kind to myself. On the other hand, if I only see my own qualities but it is hard for me to see also my miseries, I am deceiving myself and I fail to see myself honestly. Sometimes we need other people who with love, understanding and respect will tell us what we should improve in our lives, especially those who live with us and know us.

We invite you, then, to live Lent as a time of reflection, not to be depressed or full of despair as we face our own selfishness or those of others, but as a time to get ready so that when Easter comes, when we celebrate that Life has conquered death through Jesus’ Resurrection, we can do it in a healthy manner, accepting our virtues in order to strengthen them, and also our weaknesses so that it may be easier to address them.

Happy Lent!

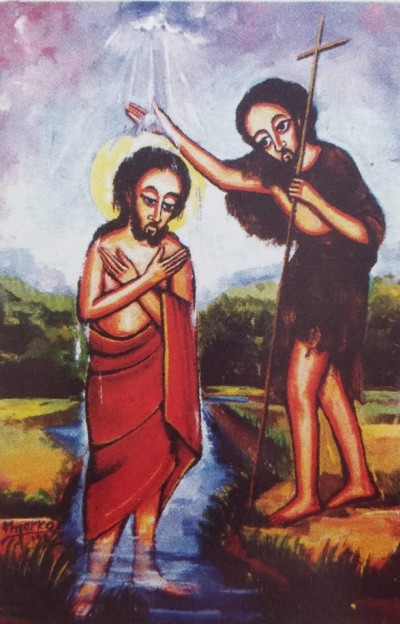

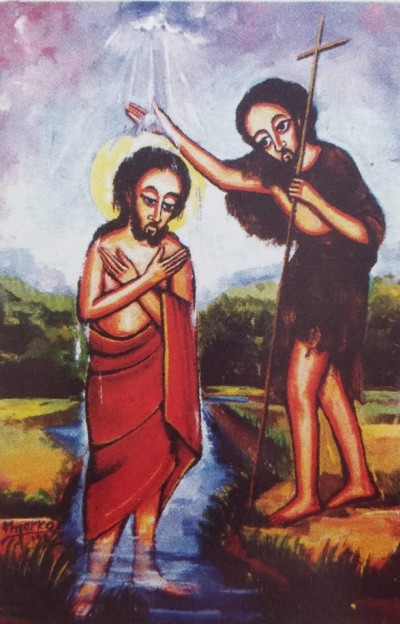

The Baptism of Jesus is one of the most important events in his life. However it is a feast, a week after Epiphany, that merely tiptoes through Christmas the celebrations, becoming perhaps one of the most depreciated and less valued celebrations of the liturgical calendar.

It could be seen as just another episode, when in fact it was perhaps the fundamental event of his life, the moment in which Christ assumed his mission and began his public ministry, most probably still without knowing the scope and significance of his decision. Popular culture makes us believe, however, that very early in His life, almost at birth, Jesus would be endowed with the capacity to be all knowing as to the events during his life. Thus, he knew in advance that he was going to be baptized by John at the River Jordan, and his mission and identity. If this is our understanding of Jesus’ self-perception, then his baptism loses its significance.

Deep down, there is a need to believe that in Jesus’ baptism there was not a rational and conscious decision but that is was somehow predetermined. To believe that Jesus didn’t have a choice, thus having doubts during his life before and after his baptism, comes from the fear of compromising his divinity making him too much like one of us. This is why, despite the fact of his humble and simple birth, we have made him a superman, endowed with superhuman powers, in this case, the power of omniscience even at his birth. The problem is that in the effort to avoid compromising Jesus’ divinity we run the risk of questioning his full humanity.

We should be careful with the superhuman characteristics that we often ascribe to Jesus to protect his divinity. In fact, the more special and super-human we make Him, the less human he becomes. In this process of "super-manning" Jesus we lose the key and transcendental element of the Incarnation and therefore of our faith: Jesus is a person like all of us, no less and no more.

True, he is also God, but the divinity of Jesus does not come from alleged super-human attributes but by his ability to be fully open to the will of the Father, by his radical capacity to love and give himself to others. This is the greatest paradox of our faith, of the faith in God made man: The more human we are, the freer we are to love, and—in a way—the more divine we become.

In sum, if in this longing to make Jesus super-human, we believe that from an early age he knew about his messianic role, his life and his fateful end, then his baptism is obviously irrelevant.

The experience of Jesus in the Jordan is not just another episode preset and known to him; it is the fundamental experience of his life. At his baptism, Jesus makes the decision to dedicate his life for the liberation of others and he recognizes himself as the Messiah. The crucial part of the baptism is that Jesus is able to change the traditional messianic expectation characterized as a victorious, powerful, exclusivist, political and religious Messiah to a universal Messiah centered on the poor and based on compassion and tolerance, not only political but for the integral liberation of the person as a historical, social, religious, cultural and psychological subject.

From the time of his baptism, through the call to his disciples and throughout his public ministry, Jesus’ mission is just trying to convey to others and to us what kind of Messiah he is and how we can imitate him. At the end, the attempt will cost him his life but will also enable us to follow him.

The parish of St. John Paul II, located in the Southside of Milwaukee, is the product of three parishes traditionally of Polish origin. Nowadays, a growing Hispanic community is added to the Polish community, and it is a beautiful experience to see how both groups, separated by different languages and cultures, try, nevertheless, to feel like a single parish. It is not a challenge easily overcome, but prejudices are broken from one side and the other every time a personal relationship of friendship is established, each time an English speaker enjoys a “taco al pastor” or prays to Our Lady of Guadalupe (and he has no qualms about trying to pronounce her name); when those born in the country know immigrant families, go to their homes, celebrate together, and appreciate and are moved when they hear the situations that many families have gone through and admire the capacity and work ethic that has led these newcomers not to falter.

We also experience the reality of integration when a Mexican celebrates the 4th of July and proudly displays the US flag at home, because despite hardships and difficulties, he knows that he has had a new opportunity here. Or when she is excited to be a member of a new parish group because she feels comfortable and knows that she will be heard. These are small signs, steps that aim at integration and mutual solidarity, which will not appear in statistics, nor in laws, nor in migratory policies. But the truth is that, not only in Milwaukee but throughout the United States, parishes become, by their very nature and mission, a privileged space for integration.

Hopefully this opportunity—this reality that we live here at the parish level—will be lived in other churches, in other centers and institutions, so that more and more groups learn how to transcend the world of prejudices and myths, to embrace the real world of people.

Today, Palm Sunday, we read the Passion of Jesus, as we will do on Good Friday. As we listen to the story we are invaded with distress and sadness, and even with some anger. The silence of Jesus can be difficult to accept. It can easily be interpreted as a signal of surrender, a fatalistic acceptance of fate. How can he fail to respond directly to either Herod or Pilate? His response to Pilate has some vague explanations about His kingdom not being of this world. Of course, Pilate does not understand. We might even think — right or wrong — that the governor was more than willing to help Him. Certainly, Jesus in the Praetorium was on trial, but he gives up his fundamental right to defend himself. We could wonder why he doesn’t answer Pilate with some witty phrase to disarm His opponents (as he has does before), or why he doesn’t give an inspirational speech to unnerve the masses? Why doesn’t he do some spectacular miracle as the people of Israel were used to seeing from Yahweh?

But no, Jesus goes to his passion “as lamb was taken to the slaughterhouse” (Is. 53.7) and that is at times difficult for us to accept. But then, after reflecting a bit, we realize that perhaps that silence was the only possible speech. Because the strategies of power, the dynamics and the spirals of envy, vengeance and hatred, can only be broken with silence, and perhaps even with death (which doesn't always have to be physical). Anything else would be like the arms race during the Cold War, to see who has “more.” Any action from Jesus would have put Him on par with the intricacies of power of Pilate, Herod and company. The only way to deescalate and dynamics of power is becoming a lamb led meekly to the slaughterhouse.

Martin Luther King, Jr., said that hate cannot drive out hate. We do not eradicate violence with violence, nor is power neutralized seeking spaces of power. We are to be witnesses of generosity and love, to show that we don't care about big or even small shares of power. That we don’t care if we don’t appear in the picture, that it's okay if we are not shown any appreciation for our actions. For some, this could be seen as a failure or even total defeat. But it is more meaningful than any victory achieved, even slightly, through the parameters of power. Maybe we will get there fully in heaven, but that doesn’t take away the fact that already, from this point forward, we should move towards that direction, toward that new Easter that is already near.

Probably Jesus, during his Passion, did wish to talk, to say something to Pilate and Herod, if only to defend his own disciples. But if he was to start arguing, then he would have joined their game. In the end, it turned out that his silence, so hard to understand at the time, was, three days later, his greatest speech and his greatest miracle.

There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.

Leonard Cohen (Anthem)

Traditionally our faith as believers and Christians, specially within the Catholic tradition, is defined and understood as a collective event. The Church, the community, the sacraments are indicators of the importance of the collective character of our faith. Even the hermit has a collective faith: the “Robinson Crusoes of faith” do not exist.

However, when we talk about the resurrection, we tend to strip the faith of its social content and we retreat to a more intimate dimension; the Resurrection seems to be confined to a personal dimension, an individual event inaugurated by Jesus. Beyond theological considerations, the following is a reflection on the meaning of the resurrection from a collective point of view. The purpose of these lines is extremely modest: to see how at a sociological level there is an association between death and resurrection, and to look at what is, then, the meaning of the latest.

Jesus’ passion was not only one man’s torture, it was not only the indescribable physical and psychological pain of dying on the cross. The unbearable torment of the cross was also a dramatic collective event. The crucified Jesus was a tragedy with deep social implications. It was precisely from this collective debacle that the nascent, frightened and weak Christian community began to live the experience of the resurrection, to gain awareness, courage, strength, and conviction; It was there that the cross became not only an instrument of torture but a symbol of life, a sign of a common struggle. The passion as a social phenomenon is somehow necessary for the resurrection of a people or a community.

In the same way that Jesus made the Passover from death to the life, analogically we can observe how oftentimes a reprehensible and unjustifiable act of violence or a social injustice are capable of bring about new life.

We don't have to look very far to find some dramatic examples of this: last February 14, we witnessed a shooting in a USA school, another tragedy to add to the heartbreaking statistic of gun victims in the country. That awful event has started a popular student movement to demand changes in the regulation of the acquisition and possession of weapons.

Another example is the recent announcement by Pope Francis about the canonization of bishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, murdered on March 24, 1980 while celebrating the Eucharist. His death helped the growth of popular movements against political and military tyrannies across South America, and elsewhere.

Still going back in time, another example was the horrific killing of a young Emmett Till in 1955, in the State of Mississippi. From the pain and rage of this racially motivated crime, African Americans responded with new strength through the Civil Rights movement in the USA.

Only five years later, in the Dominican Republic, the Mirabal sisters, three women who dared to confront the tyranny of Trujillo’s regime, were killed: it was November 25th, 1960. To honor them, that date was later chosen to celebrate the International Day for the elimination of Violence Against Women, and since then there is a growing awareness about women’s abuse, becoming, 50 years later, one of the basic demands for women’s right.

More examples could be added of people who have led to a collective resurrection through their own passion and sacrifice, such as Mahatma Gandhi, with his non-violent struggle for India’s independence and peaceful co-existence between Hindus and Muslims, or Harvey Milk, assassinated in 1978 for his political activism defending the rights of homosexuals in San Francisco. These are well known examples. There are many anonymous passions, only known and experienced at the local level, or within a group or even in a family. But in any case, they still bring about the mobilization of that group.

All these passions, regardless of how well-known they are, raise the conscience of a group or a community. It’s a jolt that wakes up sleeping consciousness, shakes up apathy and takes us out of our comfort zone, and moves us to political or social action (the resurrection). It does not need to be revolutionary or violent. The collective being moves slowly, but the initial spark, the initial movement, it’s almost always traumatic (a passion).

All collective passions, like Jesus’, dramatically reveal the cracks of the social structures, that are often hard with the weak and accommodating with the strong. But through these passions, in turn, there is always the possibility for a new resurrection, a movement of light, of hope and change. The Resurrection of Jesus is a permanent invitation to us to turn social injustice, exclusion and intolerance into life, hope and social integration.

A popular Good Friday tradition, very well-known especially in Latin America, is what we call the "sermon of the seven words." People gather in their parishes, on Friday after the adoration of the Cross, and a sermon is preached on each one of the seven words (or phrases) that Jesus pronounced on the cross in the different Gospels.

On the theological level, the cross is a liberating and salvific event, but at a historical, human, personal and psychological level, the cross was a harrowing experience for Jesus. It is, in a way, the image of total loss. On the cross Jesus not only lost his life but also his disciples, his plans, his identity, his good name, his reputation. On the cross Jesus loses everything.

The “seven words” can become, for us, a good tool in order to face our own experiences of loss. We live in a society that values success, and by it, establishes the worthiness of a person. But what we might have to learn and teach is not so much how to win but how to to lose. In fact, not knowing how to cope with our losses is the underlying cause of violence or intolerance, for instance. Both violence and intolerance are symptoms that indicate that those who practice them are not well prepared for loss. And yet, from an early age our lives are full of losses: one can lose a loved one, lose a fight, a discussion, a privilege, or a job, and it depends on how well prepared we are that we can move on after an experience of loss. We must learn to handle losses, and Jesus, in his words on the cross, can give us a clue about how to cope with our own experiences of the cross, our Good Friday, and thus prepare ourselves for the resurrection.

1. «My God, my God, why have you forsaken me» (Matthew, 27:46 and Mark 15:34). The scream is heartbreaking, devastating and shocking, coming from Jesus himself. But, it is also extremely human. It’s a cry of frustration: I can’t go on! It is a cathartic cry that, one way or another, helps us to let go. As we live our crosses it is necessary to know how to express ourselves, without repression. We have to be able to say without fear or remorse what we are suffering, at least to our own selves.

2. «Father, forgive them because they do not know what they are doing» (Luke 23:34). Every experience of loss is often accompanied by the assignment of guilt, either to others or to oneself. That is why, to be able to assume loss, we must embrace the experience of forgiveness. The absence of grudges is essential for the healing of wounds.

3. «I tell you the truth, today you will be with me in paradise» (Luke 23:43). Often the experiences of loss are, at the time, meaningless and defeat any logical explication. But we should try to discover, even in a counter-intuitive way, the positive elements that such experience can trigger.

4. «Father, into your hands I commend my spirit» (Luke 23:46). In times of loss we must recognize that we cannot always be in control of situations or other people. Letting go, knowing that events are beyond us is a way to deal with losses in a healthy way. We have to learn how to let go.

5. «I thirst» (John 19:28). Asking for help is always a way to make our crosses more bearable, recognize our vulnerability and, thus, our obvious need for others. We are not heroes.

6. «Woman, here is your son ... here is your mother» (John 19: 26-27). One of the most difficult dimensions of a loss is to accept that people around us do not have to live our situation, and even though they may show empathy toward us, we should not drag others to our own crosses or our own pits of pain.

7. «It has been accomplished» (John 19:30). In moments of loss or mourning, sometimes as a consolation we find unhelpful expressions like "everything happens for a reason" or even worse, "God has His own plans” or “this is simply what He wanted." Although unfortunate, these expressions reveal the idea that often our crosses, the sufferings that invade us at a certain moment, are doors to new paths that without them we would never have explored. There is meaning, perhaps, in our suffering.

Let us examine these words of Jesus on the Cross; let all our experiences of loss, perhaps with the help of time, be positive, so that Good Friday we may not have the last word and we may reach the Resurrection.

Esteban Redolad

As they continued their journey he entered a village where a woman whose name was Martha welcomed him. She had a sister named Mary [who] sat beside the Lord at his feet listening to him speak. Martha, burdened with much serving, came to him and said, “Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me by myself to do the serving? Tell her to help me.” The Lord said to her in reply, “Martha, Martha, you are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part and it will not be taken from her” (Lk 10:38-42).

The story of Martha and Mary has been used, through the centuries, to highlight the dichotomy between prayer and action, and to establish the distinction between the contemplative and the active life (and to give primacy to the contemplative vocation). There is however, a possible different assessment of the distinctive roles played by the two women. In the story Martha plays the typical feminine role (that is, according to the society of 2,000 years ago), while Mary becomes the prototypical disciple.

Martha was busy with all the chores that then, and still now, are expected to be performed by women in many cultures: cooking, cleaning, and house work in general. Mary, on the other hand, did what no one expected from a woman: to sit at the feet of the Master, that is, to be his disciple. And Jesus did what no master ever did: to have women disciples. “Martha, Martha”, Jesus will conclude, “Mary has chosen the better part”.

Martha was unable to move away from the chains of a patriarchal society in which her role was only subordinate. She was contented, even if she complained, with her role as a servant. Martha was debased by the weight of a male dominated culture, while Mary dared to assume a mission.

May the Marthas we all have inside, complainers but impoverished and degraded, give room to the Marys, unafraid, challengers, aware of our worth, of our potential and our mission.